Words: Kurt Bayer

Editor: David Rowe

Design: Paul Slater

Cover illustration: Rod Emmerson

Video: Ella Wilks

Motion graphic: Phil Welch

Additional reporting: Anna Leask

Click here to read:

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

A chill shuddered through Rahimi Ahmad. Fumbling in the morning dark of his home to pray, he felt his way down the hallway and realised he wasn’t feeling well. Maybe the build-up and excitement of his wife’s graduation yesterday – the product of a long journey that had brought them from the white sandy beaches of Malaysia to a post-quake Christchurch five years ago – had been too much. Rahimi had the flu.

Feed the flu. After his salat al-fajr dawn prayer, he opened the fridge. He glanced at the dozens of fridge magnets and panoramic postcards – showing jagged snow-capped peaks, lush green mountains rolling down to secluded bays. Signpost souvenirs from roadtrips, pointing to Bluff, Te Anau, Queenstown, Mataura, Gore, Murchison, and at the top, in the middle, the Ahmad family’s adopted hometown: Christchurch.

Rahimi Ahmad with his wife Azila and two children, Razif and Faiqah. Photo / Supplied.

Rahimi Ahmad with his wife Azila and two children, Razif and Faiqah. Photo / Supplied.

He picked up a purple mangosteen fruit and a pineapple in each hand. He could hear his eldest child, 11-year-old son Razif, telling him to sniff them, sniff them Dad. “You have to smell them,” he’d always say, his brown eyes glinting like the Canterbury sun off Al Noor Mosque’s golden dome. Beloved Razif, always on the brink of bubbly giggles. “The sweeter the smell, the more ripe and juicy they are.” Rahimi remembered his son’s “fun fact” from yesterday: “Turn the mangosteen upside down, you count the petals and that’s how many fruit are inside. About six, on average.”

Rahimi decided the smell wasn’t quite right, and knew his son would tell him so. So he selected a spiky rambutan – his daughter Faiqah’s favourite. The 8-year-old loved the furry, sugary fruit’s interior, which she delighted in cracking open, either with her teeth or immaculate wee fingernails.

He peeked through the venetian blinds in the road-facing lounge of their rented classic 1960s home. Red brick, white mortar, narrow driveway. He looked across to Ray Blank Park – named after the former Waimairi councillor and sportsman and home to the annual Culture Galore festival, where Azila would cook up a storm every year. It reminded him that Ramadan was approaching and he and his wife would have to start planning for their iftar feast that they’d rustle up again for about 100 University of Canterbury students. Penang-style chicken curry and biryani, pineapple and cucumber salad, pickled red onion, vegetable dahl and tempoyak, the fermented pulp of a durian fruit. The sun was coming up but all the sniffling, aching Rahimi wanted was to be back in bed.

Rahimi Ahmad, left, enjoys a meal with his family, his wife Azila Ahmad, son Razif Ahmad, standing, and daughter Faiqah Ahmad, at home in Christchurch. Photo / Alan Gibson

Rahimi Ahmad, left, enjoys a meal with his family, his wife Azila Ahmad, son Razif Ahmad, standing, and daughter Faiqah Ahmad, at home in Christchurch. Photo / Alan Gibson

He sat down at the formica kitchen table, where the Ahmads would gather and eat, at least twice a day, sometimes up to four times at weekends. Moving quietly, so as not to wake his sleeping wife Azila – sweet, clever Azila who’s knocked it off and made Rahimi glow with pride – texted his boss. The robot technician at a dairy plant said he wouldn’t be in today, there’s no way he wanted to spread the flu. No worries, get well soon.

The kids could stay home from school today, he thought. He took some medicine, retired to bed, and closed his eyes. He dreamed of his little village of Kampung Binjai in Bayan Lepas, Penang and its crystal clear waters. He was a child again, back in the early 1980s, and he and his friends were larking around and around a cocoa tree, ducking the hanging rugby-ball shaped fruit, like the ones on his All Blacks 2015 Rugby World Cup polo shirt. And when he woke, he remembered that cocoa tree, how it’s gone now, replaced by palm trees, and how he misses it so.

About the time Rahimi Ahmad was in his groggy slumber, across town Linda Armstrong was agonising over an email. She wanted to quit. It wasn’t easy and the words needed to be right.

She had given the last eight years of her life to Islam. The West Auckland-born Muslim convert had sponsored a Syrian refugee in Jordan, volunteered at a Refugee Resettlement Centre in Māngere, South Auckland, and been a vocal advocate for women's rights.

Linda Armstrong. Photo / Supplied

Linda Armstrong. Photo / Supplied

A “story-swapper”, her nephew Kyron Gosse described her, the 65-year-old with gammy knees loved sharing New Zealand with foreign arrivals, taking them to parts of the country they might never otherwise see and helping them to settle into their new home. Her perpetually tickled smile was a contagion that lasered barriers and prejudices.

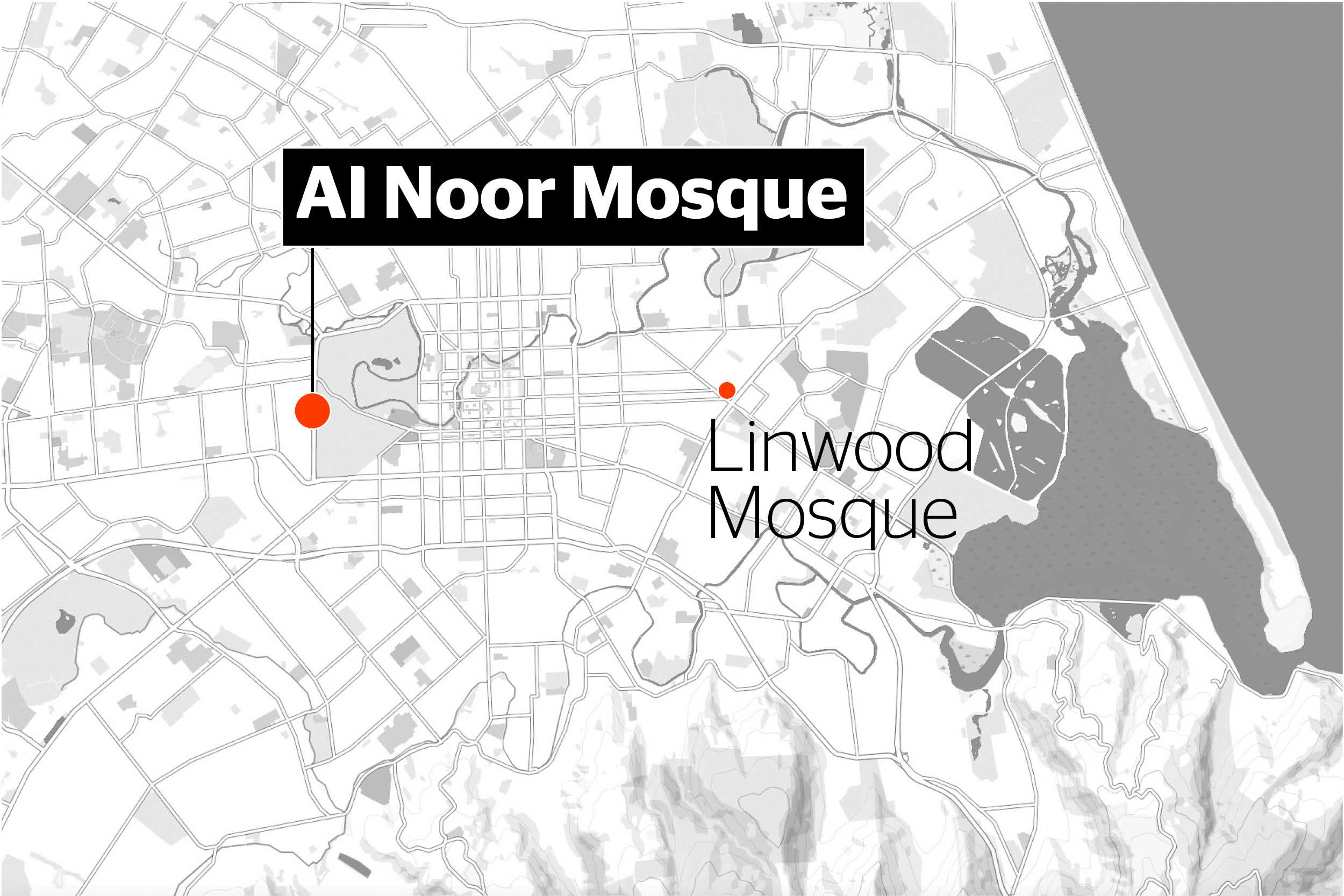

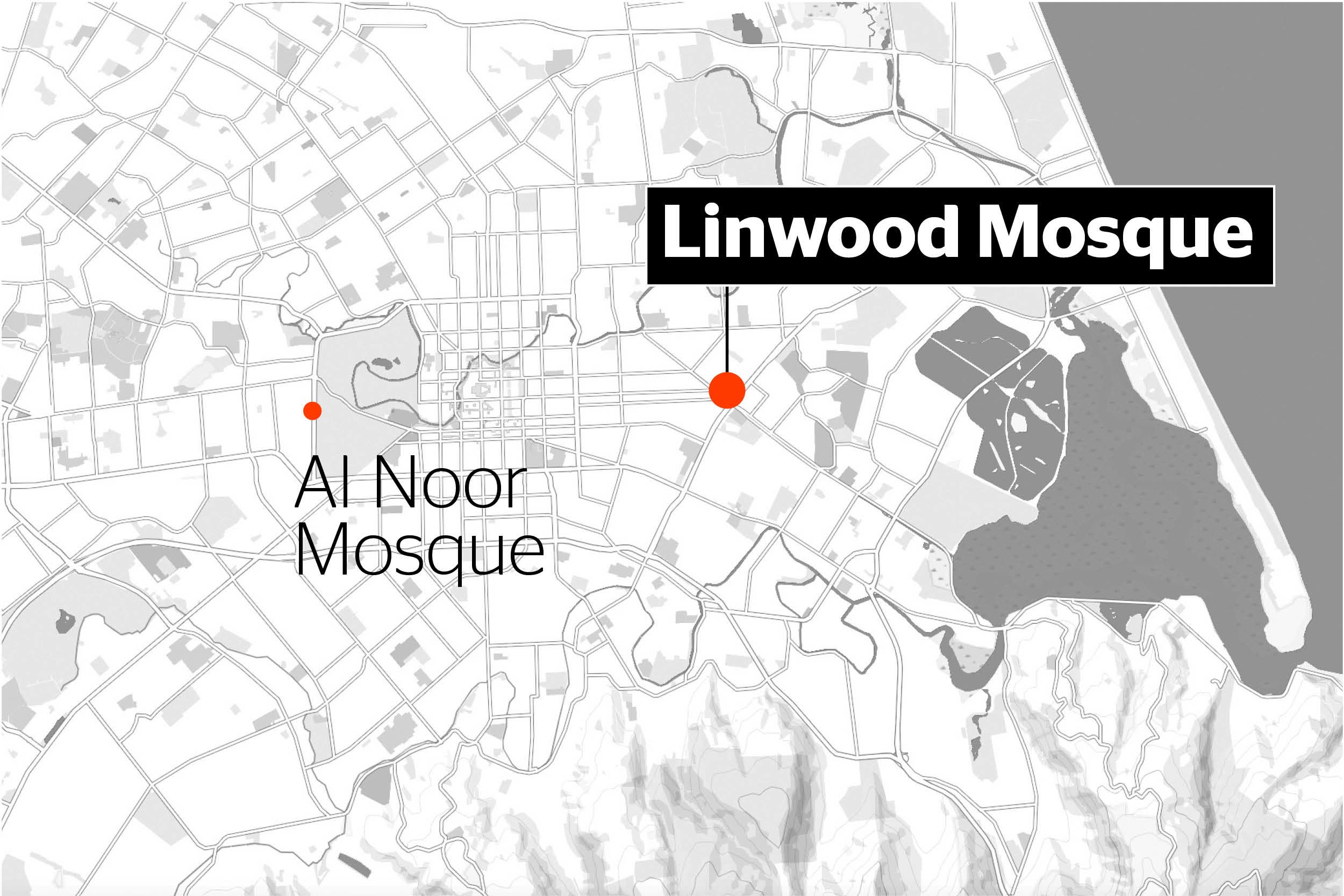

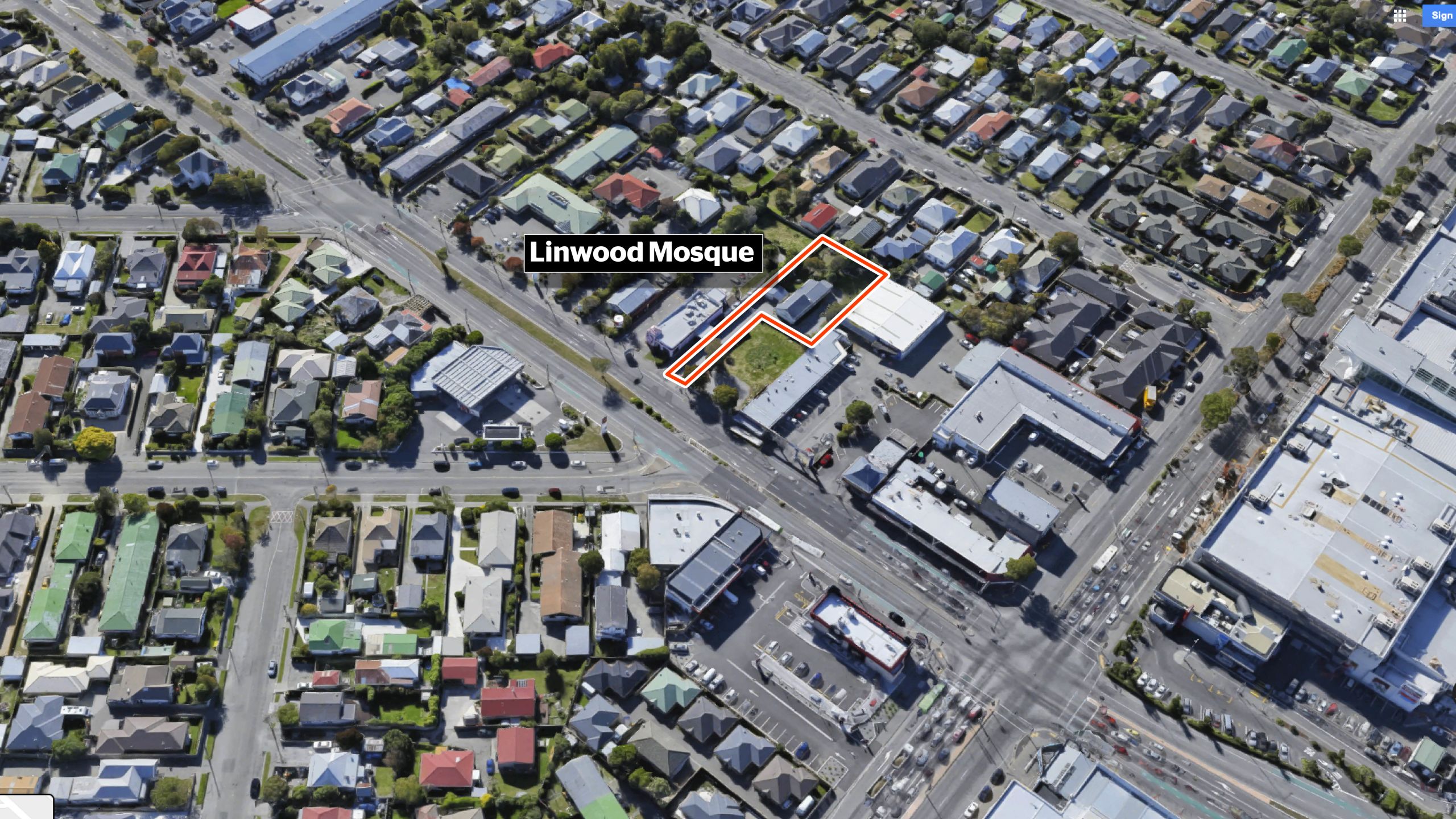

Abdul Jabbar, also a white Kiwi convert to Islam, first met Armstrong – who’d moved to Christchurch to be closer to her daughter and grandchildren – shortly after the Linwood mosque opened on January 1, 2017, in an old wooden back-section building at 223A Linwood Ave. It was designed to cater for Muslims in the east of the city and ease pressure on Al Noor Masjid, which was often full-to-overflowing for Friday prayers.

Friday prayers at the Linwood Mosque. Photo / Kurt Bayer

Friday prayers at the Linwood Mosque. Photo / Kurt Bayer

About eight months before March 15, the Linwood Islamic Charitable Trust’s Facebook page started receiving a flurry of concerning messages, according to Jabbar. Real hate messages. Things like, “We hope you die” and “We’re watching you”. It was apparently reported to police, who suggested online safety group NetSafe.

Al Noor Masjid had experienced similar things over the years. Local white supremacist Philip Arps was filmed delivering boxes of pigs heads – pork is considered unclean by Muslims - to the mosque just three years earlier. The video, intended to be shared within a 20-strong cell of local neo-Nazis, shows Arps declare: “White power, my friends, my family, my people. Let's get these f***ers out. Bring on the cull."

Arps, whose business Beneficial Insulation features various Nazi symbols and white supremacist messages, was convicted of offensive behaviour and fined $800.

Christchurch has always endured a racist reputation. Skinheads, neo-Nazis, a seedy underbelly of hate. Asian students jumped and bashed walking home. Dogs unleashed on tourists. In 1989, skinhead Glen McAllister shot and killed an innocent bystander.

Extreme right-wing anti-immigrant groups like The New Zealand National Front held marches and protests. Hitler T-shirts in Cathedral Square. Sometimes, the peaceniks showed up and chased them away.

Then, they all seemed to just disappear. But did they? Or did they just go deeper underground?

Meanwhile, Sister Linda was becoming a key player at the Linwood Islamic Charitable Trust. The former member of New Lynn mosque became treasurer and volunteered at every garage sale. When the Nelson fires in February last year forced hundreds out of their homes a month ago, she drove in a car load of essentials to help out. And lately, she’d taken in a young Indian man to help him get back on his feet.

“She was a determined woman of very strong faith, which gave her a strength and a courage,” Jabbar said. “She’d do anything for anybody. If someone came to her in need, she would do anything to help. She came from the white middle-class and used that to help people.”

But over time, she’d become disillusioned by the Linwood hierarchy and felt undermined, swept aside. By Friday, March 15, she’d had enough.

“I have decided to withdraw from the Trustee meetings. I’m still happy to be treasurer, and help in any way I can, but these meetings are making me ill,” she would write.

Armstrong felt she wasn’t being appreciated or listened to. “My ideas get squashed, without even a discussion about them.” At one meeting, she suggested that children who attend the masjid could be given pictures to colour in, and keep them occupied and entertained during the sometimes lengthy sermons and meetings. But before she could finish, a brother cut her off: No.

They would make a mess. OK, what about a silent auction as well as a spoken auction? No, there would be just one auction. What about an Arab-style entrée for one of their events? Subject changed. No discussion.

“I am told that I am respected and appreciated,” she typed. “I don’t see it myself. Did you know that 95 per cent of women’s greatest complaint against men is that they do not listen? And being listened to is the greatest form of respect and appreciation.” She looked over her carefully drafted email and at 12.16pm pressed send. She would be dead within two hours.

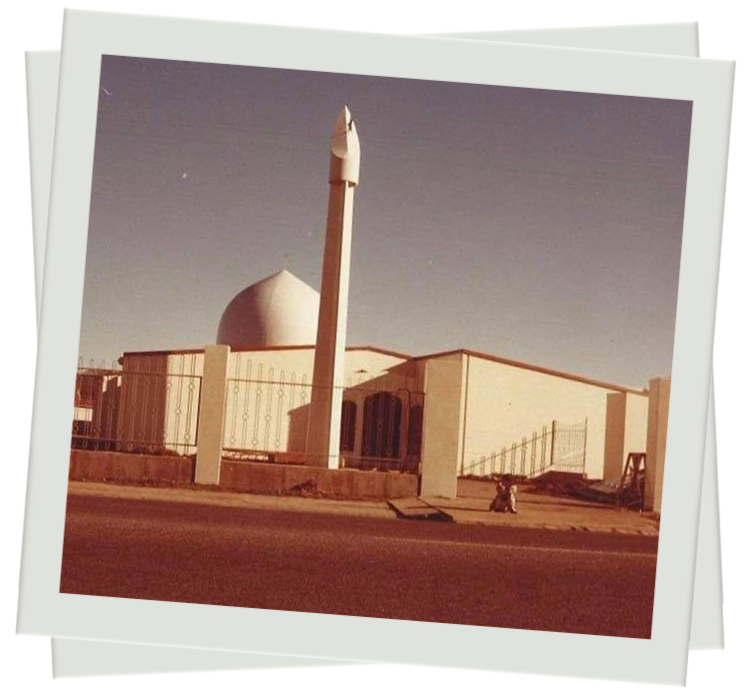

Suleman Ismail Kara came to Christchurch from India in 1948, following the trail first blazed by his grandfather 60 years earlier.

"We have a very long history here in Christchurch, that not many people know,” he says.

For many years, Kara says, it felt like his family was the only Muslim one in New Zealand's second largest city. There was no mosque and they used to pray at his house and friends' places.

After some years, they managed to scrape enough cash together and buy a Tuam St property in central Christchurch where they congregated for prayer.

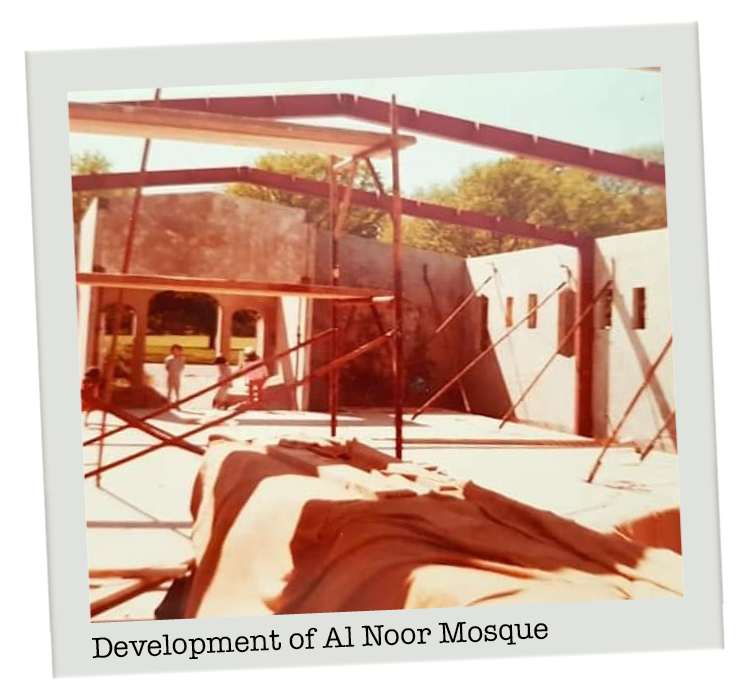

By the late 1970s, the Muslim Association of Canterbury was founded, with Kara involved, and they started planning a proper place of worship.

They began asking around for donations, and a major boost came when the Saudi Arabian government chipped in thousands. More money followed from other Gulf nations, but it was local Muslims – who numbered less than 200 – who dug deep into their pockets and got it over the line, Kara said. They ended up raising $700,000 and building what was, in the mid-eighties, a state-of-the-art masjid.

"It didn't matter how much people gave; if it was a dollar, it turned $99 into $100. It all counted the same," Kara says. "It was done with the help of God and the people who donated to it. It was everyone all together. It doesn't matter if it was someone coming to sweep the place, he's just as important as anyone else."

It was a slow build. First the association acquired the 101 Deans Ave land, across from the jewel in the civic crown, Hagley Park, 165 hectares donated to the city by early settlers "reserved forever as a public park, and open for the recreation and enjoyment of the public". The Mayor of Riccarton, RWJ Harrington granted permission for a mosque after a lively borough council debate, where one member was concerned about a mosque sprouting up in his neighbourhood. But Mayor Harrington laid the fears to rest, when he cited the church next door, to which nobody had objected.

The plot of land was fenced off, and they waited for more cash to come in. They poured the foundation and hired architect Rasjid Wallen, who travelled globally, taking inspiration from India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Arabian mosque designs, before canvassing local views. They plumped for a copper roof and striking, traditional gold dome. It included a main prayer hall for some 300 worshippers, a lecture room, community and committee rooms, plus a library.

Christchurch's first mosque – then the most southernmost in the world – officially opened in November 1985. The first imam was Osman Gaafar, a post-graduate student at Lincoln College, originally from Sudan.

"We have an open-door policy and we welcome interest from non-Muslims," Razzaq Khan told The Press newspaper at the time. Khan said Christchurch now had a 300-strong Muslim community comprising of 28 nationalities speaking 28 different languages and welcomed the opportunity to tell reporters "what Islam is really about".

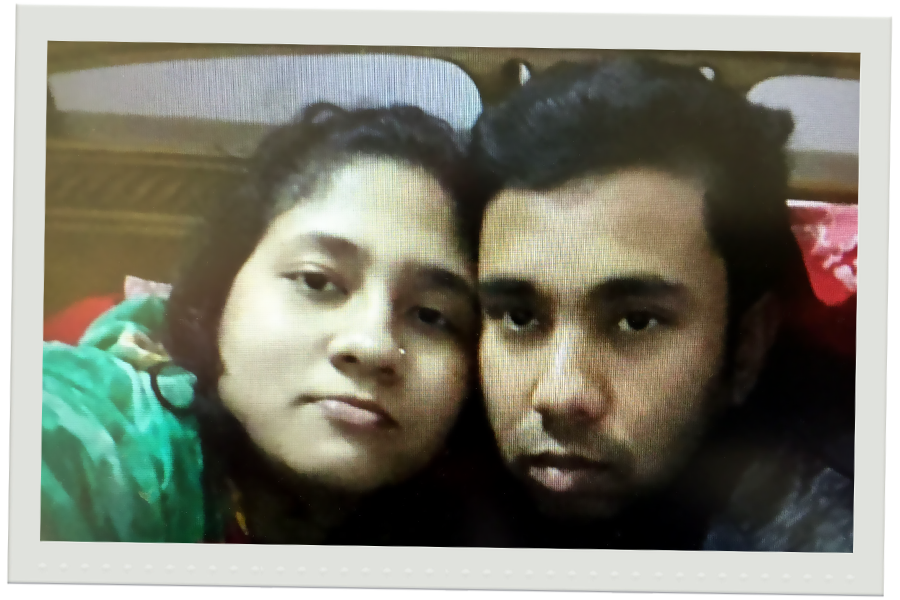

Very late at night for her, with Bangladesh six hours behind New Zealand time, Sanjida Neha kept calling. She was restless. Pregnant with their first child, she was excited and nervous and wanted to hear her husband Mohammad Omar Faruk’s reassuring, calm voice. Mates say he'd been glowing with pride.

Omar was up early to be at work at 8am that day and asked his wife nicely if she should get some sleep. He told her he expected a long day working outside at a construction site on a moody autumn day. It was humid but temperatures were only in the high teens. It felt like rain.

But it wasn’t humid like back in Narayanganj, a city of two million people near the Bangladesh capital of Dhaka, where they both were from. Their families knew each other and when Sanjida, studying business administration, was told her marriage with Omar was arranged, she was delighted – even though she’d never seen him before. He’d left a couple of years earlier after a good welding job took him to Christchurch, via Singapore, where he’d worked for a few years.

Sanjida Neha and Omar Faruk. Photo / Supplied

Sanjida Neha and Omar Faruk. Photo / Supplied

So when she finally laid eyes on him one week before their wedding, she was overjoyed with the match.

"We were very happy, very excited," she said.

They got married in Bangladesh on December 29, 2017. Wedding photos show the couple in traditional dress. Afterwards, Omar looks sharp in a dark suit.

After a long holiday in newly wedded bliss, Omar returned to Christchurch, and his job, in February last year.

He worked hard all year. Omar and Sanjida spoke everyday via video calls and talked of their plans.

Omar wanted to finish building work on their family home where they talked about living in the future. But they also thought about coming together in Christchurch.

Omar Faruk. Photo / Supplied

Omar Faruk. Photo / Supplied

In November last year, he returned home for an eight-week holiday.

Sanjida soon fell pregnant.

While in Bangladesh, Omar worked hard on the house, and was keen for his wife to stay indoors as much as she could to avoid sickness and any complications.

It was a gruelling wrench when he had to return to Christchurch on January 18.

But at least they could speak every day. It made Sanjida feel like she was there with him. Except, she didn’t think Omar was going to the mosque that day, what with the big job on at work. But around midday, it started to rain. And his boss said he may as well knock off early. Omar's eyes lit up. He hardly ever got the opportunity to attend Friday prayers at the golden-domed mosque across Hagley Park - work came first and his religion allowed that. He would usually just pray in his own time. So he took the chance to pray. And be thankful for all he had in this life.

By noon, Rahimi was starting to feel better. A hot shower had perked him up. He thought about having lunch before going to Jumu'ah, or Friday prayers, at the university as he’d normally do. But since Razif was home from school with him, he decided to take his son with him to the main mosque in town, Al Noor Masjid on Deans Ave.

They parked in the rear car-park and went through the side door about 1.15pm. Normally, Rahimi liked to sit in front of Imam Gamal Fouda’s minbar, the wooden pulpit where he delivers his sermon.

But that day, for some reason, he chose to sit two rows from the exit door. The decision probably spared his life. “All I can think is that Allah wanted to save me.”

Farid Ahmed was tired. He would have been late if his wife Husna hadn’t been there, as she always was for him. While he rested though the morning, she’d been busy; dropping 15-year-old daughter Shifa at school; cooking and chatting with friends on the phone. Husna helped get him ready, eased his wheelchair into their car, and headed off to Al Noor. They chatted about their family and lives on the way.

Farid Ahmed. Photo / Mike Scott

Farid Ahmed. Photo / Mike Scott

After a drunk driver crashed into Farid and left him paraplegic 21 years earlier, they made a decision to lead their lives however they wanted. Husna wanted to be a full-time volunteer, helping women, children, neighbours, communities. They both took classes at the mosque every Saturday and Sunday. They shunned holidays, preferring to give to others. It's what they loved.

Husna Ahmed. Photo / Supplied

Husna Ahmed. Photo / Supplied

Just after 1pm, they pulled into a special car-park reserved for them. Husna headed for the women’s room while Farid wheeled himself inside. Making for his usual spot in the main hall, he noticed a brother who had been having a tough time with cancer treatment. He stopped to spend some time with him and, as they talked, prayers began, so Farid stayed in the side-room.

Hagley Park. Photo / 123RF

Hagley Park. Photo / 123RF

With watery early autumn sun streaming through the seventh-floor Christchurch Hospital windows, Dr Hayley Waller thought her kids might like an ice-cream after school.

Outside below, the leaves had yet to change in sprawling Hagley Park, or across the meandering Avon River, in the peaceful green spread of the Botanic Gardens. Jackhammers and drills working on the new post-quake CBD buildings scattered birds and broke the calm of a Friday afternoon, a Canterbury weekend looming with possibility.

Dr Hayley Waller. Photo / Kurt Bayer

Dr Hayley Waller. Photo / Kurt Bayer

Just 750m away, a heavily armed man parked his car outside Masjid Al Noor mosque.

Back towards town, intensive-care unit nurse manager Nikki Ford was enjoying lunch. Registered nurse Ruth Deal was driving to work, hoping to quiz the librarian for her post-graduate studies, while surgical nursing manager Nicky Graham was sorting the latest issue cropping up on her ward.

Old rugby mates, Senior Constable Jim Manning and Senior Constable Scott Carmody, were in town from their country postings for a training day at Princess Margaret Hospital. Some SAS boys and Police Special Tactics Group (STG) officers were also in the city, about to enjoy a beer on the Strip.

Exactly how many people were inside Al Noor when the gunman entered is not known. Estimates range from 200 to 400.

Omar Faruk’s old flatmate and fellow Bangladeshi and welder Mojibur Rahman had been off work ill that day. But, like Rahimi, he’d perked up around lunchtime and at the last minute decided to attend Friday prayers.

Prayers at Linwood Mosque. Photo / Alan Gibson

Prayers at Linwood Mosque. Photo / Alan Gibson

But as he walked up to the mosque’s rear entrance, he spotted a man with a large gun walk up Deans Ave, and turn into the front gate.

He didn’t stick around. Rahman ran for his car and sped off.

The first 111 call to police came from a member of the public at 1.41pm. Imam Fouda was a few minutes into delivering his sermon from his elevated pulpit when the gathering jumped at what sounded like three gunshots.

Al Noor Mosque Imam Gamal Fouda conducts Friday prayers. Photo / Mike Scott

Al Noor Mosque Imam Gamal Fouda conducts Friday prayers. Photo / Mike Scott

The congregation’s leader wondered if it was some of the youngsters playing around or noise coming from the sound system. But then another shot was fired, this time closer.

Rahimi tried to grab Razif’s hand but the youngster had bolted. Frantic, he looked about, searching for his son. He decided to run after him but had taken just one step, before a hot flash splashed his right hip, near his back.

“I am shot in the first round the shooter has come in,” Rahimi recalls. “I just lay on the floor holding the place where I’ve been shot, thinking where did my son go?”

Many, like Rahimi, played dead. He had a dead body fall across his back, another draped across his legs, and another 10 bodies lying all around him.

Husna Ahmed decided to take a chance. She snuck out of the room and, when the coast was momentarily clear, started ushering others to safety.

Shouting at them as urgently as she could, they listened and bolted, turning left down the hallway, past bodies, out the front door, out the front gate and away and away, don’t look back.

Ducking the shooter’s scope, now she needed to find her husband. Later, one friend would tell Farid that Husna entered the main hall three times trying to find him. He wasn’t in his usual spot on the right-hand side of the main hall. Now, in that corner were bodies and shattered glass by a broken escape window. One young man who’d been knocked out was coming too when he heard Husna yelling at him, “Why are you here? Run! Get out!’” And he ran.

Another wounded witness, lying shot and bleeding later told Farid it was then that his wife – a woman he described as being “prepared to give her life for other people” – was gunned down.

Parked down the road on Moorhouse Ave, Mojibur Rahman started phoning around. Like Neha, he didn’t think Omar would’ve been at the mosque, given his work commitments.

Only later did sketchy details of what exactly happened start to emerge.

When the shooting started, Omar and his friends also tried to escape.

As they ran for their lives, Omar was shot in the back. Another friend Motasim Billa was wounded in the thigh. Monir Hossain had a close shave, with bullets slicing through his T-shirt but missing his body.

Another mate, Hasan Rubel, couldn’t get out of the mosque’s main hall in time and was shot in the stomach and legs. He’d spend six weeks in hospital.

Omar was not so lucky. Neha was later told he died on the spot. But it took her an age to find out if her husband was alive or dead.

Temel Atacocugu, a former Turkish soldier and kebab shop owner, was shot nine times, in the face, legs and hips, and in the left arm three times. As he fell to the floor, he thought, “Oh my God, I am dying.” The smoke and noise was chaotic, deafening, ringing in their ears. And then, all of a sudden, there would be silence.

Police escort witnesses away from Al Noor Mosque in central Christchurch. Photo / AP

Police escort witnesses away from Al Noor Mosque in central Christchurch. Photo / AP

Terrified men, women and children scattered in all directions. Some ran across Deans Ave and into the vast, green haven of Hagley Park and kept running, not daring to look back. Others who went out the rear exit or through the smashed windows felt trapped in the carpark and started clambering over fences.

Next-door neighbour Len Peneha had popped home for lunch when he started hearing gunshots. Heading upstairs to the second floor of his townhouse, he could see people “scattering everywhere”, with some trying to climb the 2m-high concrete wall over to his place. He bolted downstairs and started dragging people over the fence.

Peneha, 53, helped at least 10 people over the wall. He ushered five inside his house and told them to stay put. But there was one man he couldn’t help. All he could see was a hand clinging to the top of the wall. Unsure whether he was shot and unable to pull him over, Peneha couldn’t get the leverage to haul him to safety. He kept ducking, feeling that bullets were zinging and ricocheting through the air. But he couldn’t help that last guy. And he doesn’t know what happened to him. “I had to leave him. It still bothers me actually.”

Len Peneha. Photo / Mike Scott

Len Peneha. Photo / Mike Scott

At 1.46pm, after six bloody minutes that would change the face of New Zealand forever, the gunman left the mosque. But before he got back into his car, and headed for Linwood Islamic Centre some 7.3km east across the still unsuspecting city, Peneha saw him raise his gun one more time.

A woman was sprinting for her life and as she crossed Peneha’s driveway onto Deans Ave, he saw the gunman shoot her dead.

Looking down the driveway to Len Peneha's former home. Photo / Mike Scott

Looking down the driveway to Len Peneha's former home. Photo / Mike Scott

It took the shooter just six minutes, in broad daylight Friday traffic, to make it to the Linwood Mosque. They always held their Friday prayer slightly later than Al Noor, to give east-side Muslims a chance to make either service.

About 80 worshippers had piled into the white wooden building, up the long driveway, beside the old KFC, back when it was a Kentucky Fried Chicken. Imam Ibrahim Abdul-Hali was deep into his Jumu'ah when loud distinctive pop sounds came from just outside. The big Nigerian Alabi Lateef Zirullah, who occasionally stepped in as the imam, looked out the windows and saw that a husband and wife had just been shot dead.

Everyone was stunned mute and immobile as the gunman – unsure where the main entrance was – came to the wrong side, the southerly side, and shot another man, who’d been standing, in the head through a window.

Sister Linda, who never enjoyed being stuck behind a screen erected to separate the women from the main assembly, had earlier come forward to listen to the prayers.

Linwood Mosque Imam Alabi Lateef Zirullah. Photo / Kurt Bayer

Linwood Mosque Imam Alabi Lateef Zirullah. Photo / Kurt Bayer

As the gunman circled around the building, he finally found the front door, where Armstrong confronted him, pleading, “Please, go away.” Armstrong was shot dead just inside the main entrance.

But now, Afghanistan-born antiques trader Abdul Aziz had sprung into action. Scrambling for anything to defend his fellow Muslims, Aziz grabbed an Eftpos card reader and chased after the rampager, passing dead bodies lying in the driveway. As the attacker went to get a fresh gun from his car, Aziz hurled the card reader at him.

Getting within metres, the shooter aimed at Aziz and fired, narrowly missing. He’d report hearing the whoosh of bullets pass his head. Aziz ducked and dodged between parked cars, picking up a discarded gun and trying to fire it. Click. He shouted, “Come! I’m here!” trying to get his attention as the gunman went back to the mosque and started shooting again.

Alabi Lateef Zirullah with Abdul Aziz, left, outside Linwood Mosque in the wake of the attacks. Photo / Alan Gibson

Alabi Lateef Zirullah with Abdul Aziz, left, outside Linwood Mosque in the wake of the attacks. Photo / Alan Gibson

As the gunman took off down the long shingle drive, Aziz chased him, hurling insults, throwing an abandoned gun, like a spear, through the front windshield, shattering it, as he sped off, scared. Aziz pursued holding one of his guns, chasing the car down the street to a red light, before it made a U-turn and sped away.

And then, it was all over.

End of Chapter One.

Click here for Chapter Two:

WHAT HAPPENED NEXT

WHERE TO GET HELP

If you or someone else is in danger, call 111. If you need to talk, these free helplines operate 24/7

Depression helpline: 0800 111 757

Lifeline: 0800 543 354

Need to talk? Call or text 1737

Samaritans: 0800 726 666

Youthline: 0800 376 633 or text 234