The Crash

In October 1987 a stock market crash shook the world.

Nowhere was hit harder than New Zealand.

Thirty years on our economy still bears the scars.

Words by Liam Dann, design by Paul Slater, motion graphic by Phil Welch.

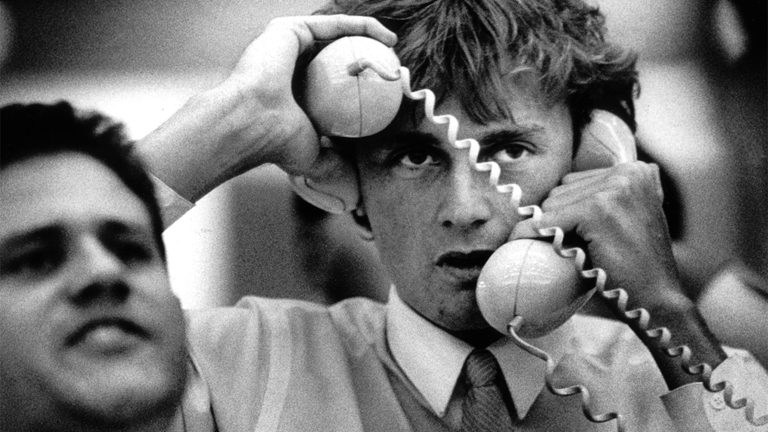

“We’d had over a week of nervous signals but this day was different,”

says investment banking veteran Rob Cameron.

In 1987 Cameron, who would go on to lead the reform of New Zealand’s capital markets after the global financial crisis of 2008, had just shifted from Wellington broking firm Jarden & Co to help set up the investment banking arm at Fay, Richwhite.

“I was sitting not far from the trading desk,” he says. “I recall listening to our operator on the floor of the exchange and the noise and the chaos and his level of excitement. He was conveying the idea that these were fantastic buys coming up, then asking us to hold just a minute because the buys had got better.”

That was the moment it became obvious that things were serious, he says.

In the US it is known as Black Monday — October 19, 1987, the biggest one-day fall in the history of the stock exchange.

Thirty years ago this month, in the era of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, yuppies and banker chic, the financial world collapsed.

But unlike 2008, history records the 87 crash as a temporary aberration, a dramatic blip in the decade of excess.

Except, that is, for one small South Pacific nation in the grip of radical economic reform and deregulation.

In New Zealand, the damage was done on Tuesday, October 20.

The country, which had been swept up in the free-market fever of the 1980s, awoke to discover that much of the new wealth that had been created was an illusion.

Our market plunged 15 per cent in a day, but that was just the start.

Rob Cameron

While Wall Street’s 22 per cent fall on Black Monday shocked the world, it was short lived. The financial system did not seize up, the great Western economies did not stall.

Even now, there is no clear consensus on what caused the plunge. There had been a rapid rise on Wall Street that had started to diverge from the fundamentals of the economy. There were growing fears about soaring inflation and interest rates. A correction may have been due, but the scale was unprecedented.

The relatively recent arrival of computerised trading platforms has been blamed for exacerbating the big fall.

One thing that isn’t in doubt is that it hit New Zealand harder than anywhere else in the world.

Most major markets started bouncing back within weeks. The US economy grew through 1988 and Wall Street was back at pre-crash levels by 1989.

But by the end of February 1988, New Zealand’s market had fallen almost 60 per cent from its peak.

It took years to recover. In fact, on a capital index basis — without factoring in dividends — the local stock exchange has never topped its 1987 peak.

The economy went into recession in 1988 and, perhaps most damaging of all, a generation of investors — the baby boomers — turned away from capital markets and put their savings into property and property focused finance companies.

“It was a period of great social change,” says Cameron. “And there was euphoria in markets.”

Des Hunt

Sir Robert Muldoon

Sir Roger Douglas

In 1984 the new Labour Government had unshackled New Zealand from an era of regulation — currency control, import licences, carless days, wage and price freezes.

The cultural and social change in New Zealand coincided with one of the great global stock market runs. On Wall Street, the Dow-Jones Industrial index rose 282 per cent between 1982 and October 1987.

“I think they’re [the 80s] probably the weirdest decade, not just for hair and clothes and music, but for economic policy in New Zealand,” says University of Auckland professor of economics Tim Hazledine. “We started off with Muldoon in charge and he did his various silly things and then we had Rogernomics.

“So we had a reformed economy and no one really knew how to plan it, I don’t think. They were unstable times.”

In the space of three years the country floated its currency, removed tariffs on imports and subsidies for farmer. The top tax rates were slashed and financial markets were deregulated.

As a result, capital poured into the country but numerous domestic businesses struggled to remain profitable.

Investment companies specialising in takeovers and restructuring jumped on to the stock exchange, raising money from the public to buy up struggling companies, including state-owned companies that the nearly bankrupt Government was racing to sell.

More than 200 companies were floated on the exchange from 1983 to the end of 1987.

By comparison, there have been just 34 initial public offerings (IPOs) on the NZX since 2012.

“It all happened too quickly,”

says Des Hunt, a longtime investor and founding member of the NZ Shareholders Association.

Hunt was working for the then-unlisted manufacturer Tru-Test at the time. He did not get sucked into the hype, despite wondering at the time whether it was him who was the fool.

“My first memory was, we were working our butts off exporting and building a business and thinking: how can all these people have so much money?” he says. “I couldn’t get my head around the valuations.”

He recalls people trying to sell him shares with valuations of 50 or 60 times earnings. It was a stark contrast to his down to earth manufacturing business, which he recalls being valued at just five to seven times earnings.

“What surprised me and frightened me was that everybody thought that it was easy to make money, so they were buying shares on the assumption they’d go up automatically, with little research,” he says.

“There was nothing behind the businesses in some cases. I think the banks, the brokers, everybody was pushing hard. They were just saying you can’t miss out.”

But it would be wrong to say that nobody could imagine a crash in 1987.

The Herald business section’s 1986 year in review described an unprecedented bullishness amongst local investors. It noted that “white heat” in the market had some pessimists predicting a crash, but that the crash hadn’t happened and “the more optimistic were borrowing to invest more.”

“Through 1986, the share market became something of a national pastime,” says the article dated January 2, 1987. “Many average citizens flocked to the new off-course substitute TAB in the hope of catching profits before they were gone,” the article noted somewhat prophetically.

By February 1987, the New Zealand Stock Exchange estimated that between 12 and 15 per cent of the population were share investors, ahead of Australia with 8 per cent.

Professional director Linda Robertson had just returned from her OE in 1987 and was working in a currency dealing room at the time of the crash.

“I recall coming back and everyone was talking about shares. ”

“Everyone was abuzz with share trading, there were share clubs. That was all very new.” In the dealing room, she recalls the crash being triggered by news coming out of New York.

“We had the benefit of a few Reuters screens. So we were quite well informed and we could watch what was happening . . . we didn’t have CNN, we didn’t have financial news channels, there was no internet.”

– Linda Robertson

And there weren’t many experienced dealers around, she says.

“We had a market-led economy, which was new for NZ. Many of us were straight out of varsity and we were all looking at each other ‘oh my God’. It was very much learn as best as you can and do the best you can.

“We didn’t have the sorts of controls and checks and balances we have nowadays,” she says.

“We didn’t have the continuous disclosure requirements. Insider trading wasn’t even illegal in those days [laws were passed in 1988]. It was really was buyer beware.”

With hindsight, Cameron puts the exaggerated rise and fall of the New Zealand market down to two major factors.

“We ended up with a corporate sector that was on average taking on higher business risks than other Western economies,” he says. “Because the liberalisation of the economy meant that a lot of resources were directed into shifting resources around the economy. That tends to be risky activity.”

“The second part of it is we had accumulated much higher leverage ratios than comparable economies ... probably at the private level but certainly at the corporate level.”

Compared to what New Zealanders were used to during the regulated banking environment of the Muldoon years, borrowing was suddenly easy, but that didn’t mean it was cheap.

Interest rates soared through the mid-1980s as the Reserve Bank attempted to tackle double-digit inflation.

By the second quarter of 1987, inflation was running at 18.9 per cent. Floating mortgage rates were above 20 per cent.

Unlike 2008, when central banks slashed rates to revive the economy, there was little room to move.

By January 1988, mortgage rates were still above 19 per cent. By October that year they remained above 15 per cent, even though the economy had stalled and CPI inflation had plunged to 5.6 per cent.

The cost of servicing debt on assets that were falling in value — or in some cases worthless — was crippling.

We’ve always had an issue with investing in property, says Cameron. “But what was worrying from a personal point of view was that property became a platform for people to leverage into the stock market and there were some people who lost all their wealth and their livelihood.

“They leveraged their homes, or in some cases leveraged their farms. I recall an incident where I had a chap ringing me up — probably starting a month before the crash — and he told me he had two farms, both of which were heavily leveraged, and he was investing in a diversified portfolio, and when I asked him what it was ... they were all Brierley shares.

“I said this is a high risk you are taking — you should think about how you manage that — and he was constantly checking on that decision and he got caught.

“His case would have been much more typical [to NZ] than to other economies.”

At the time there was very little focus on financial markets offering high quality choices, having good price discovery, having vehicles that ordinary retail investors could understand and participate in safely, Cameron says.

“I think people have described elements of it as Wild West — and probably some of it was.”

But there was also an element of bad luck for New Zealand, he says. “In the sense that, had there not been a global bull market going on at the time, the effect on our economy would have been much more moderate.”

There were people who were amateurs who were caught out, say Hazledine. “But in a sense everyone was amateur then because the whole big game of privatisations and big buyouts was fairly new to New Zealand.

“But this wasn’t a real game; this was a paper game. There were bankruptcies and stuff but it wasn’t really what the real economy was doing. It wasn’t like GE going broke — the big industrial firms like Fletcher Challenge, they weren’t going broke.”

For that reason he’s not convinced that the economic woes New Zealand went through after the crash were all caused by it.

There was over-exuberance, he says. “But we should remember that we’ve had a well-functioning stock market for about 100 years before that. We weren’t a socialist country; we were a capitalist country with a lot of controls on it.

“So it wasn’t like what happened in Soviet Russia and stuff. It makes it a little bit harder to explain.”

Nevertheless, the housing market stalled. Unemployment rose and confidence plummeted. Gross Domestic Product, which had grown at 1.6 per cent in 1985 and 2.7 per cent in 1986, ended 1987 up just 0.9 per cent. By the end of 1988 we were in recession, with a decline of 0.4 per cent. Growth didn’t climb back above 1 per cent until 1992.

Could we see a crash of that scale again?

“Definitely,” says Hunt. “Although I think the biggest risk is the housing market. Let’s say that interest rates go up, people start going back to Australia as they’ve done in the past, immigration slows down because things are going well overseas, then you suddenly got too many houses.

“You could see a 20 per cent dip quite easily. People basically like to make an easy buck. And there is no way of doing that long term.

“People just need to be careful, that’s why diversity is critical. People should take more interest in their KiwiSaver. What industries is it in? How good are the managers?

“You can’t expect 15 - 20 per cent like we’ve had the last 8 or 9 years.” Says Hazledine: “I never predict. I suppose I should wonder because my pension fund is in that too .

“One thing that is different now is that our shares tend to be dividend oriented,” he says. “Not growth shares, but income shares.

“In 87 we thought we’d have a capital growth market. They weren’t going to ever pay dividends; they were rubbish to start with. Whereas I don’t think the companies we’ve got in New Zealand now are rubbish.”

For Cameron — one of the architects of the current regulatory system, including our Financial Markets Authority — there is no question.

“Look, the one thing I can tell you with confidence is there will be another financial crisis. It is in the nature of humans.”

“We are our biases — probably a lot of them evolutionary — and they will lead to periods where we become overly optimistic about asset prices, and we’ll find ways which no-one’s ever thought of yet to come up with financial innovations that fuel it.”

It’s something to consider as the nine-year bull market, both here and on Wall Street, rolls on to new record heights.