Death on the street

Corazon Miller explores the life and untimely end of Rangi Carroll — university graduate, author, peer support worker, photographer ... and streetie.

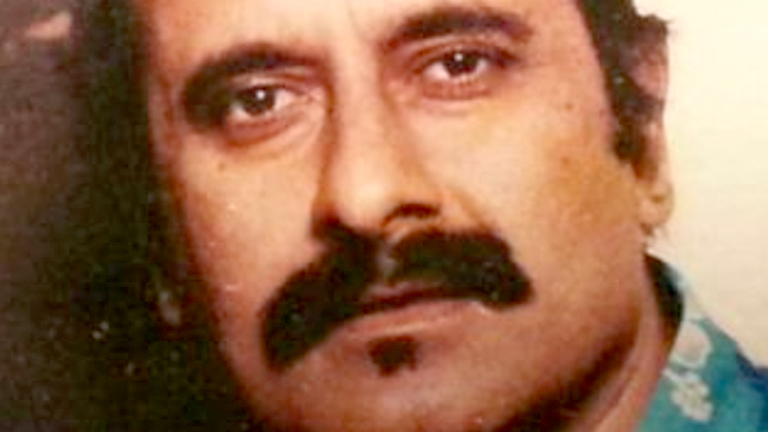

Home for Rangi Carroll was the cold, grey concrete of Auckland’s CBD. For five years his bed was a rumpled sleeping bag, his roof the open sky, his walls the inner-city facades and his family and friends were his fellow streeties. But the 57-year-old refused to let how he lived on the city streets shape the way people saw him. “My life is far from destitute ... I’ve become known as someone who achieved anyway,” he told a crowded room at a 2015 TED Talk in Hamilton.

Carroll’s name could be found in almost all of the Auckland City Mission’s activity books; a constant presence at art class, drama club, movie club, client committee and council meetings.

But one thing he seemed to struggle with was getting a job.

Carroll spent five years living on the city streets before he got into a house. But less than a year later he was dead, at just 57.

His life had ended, like so many streeties, more than 20 years earlier than the average life expectancy of New Zealanders.

If death had come to Carroll mere months earlier, it would have happened on the streets. He would have become another homeless death to shock the headlines for some 24 hours before the spotlight moves on.

Instead his death went largely unnoticed by all, except those who knew him best. It became part of the largely invisible toll that homelessness takes on those who’ve lived it, even long after they’ve left the streets.

Those who knew Carroll have little doubt his time spent sleeping rough contributed to him dying years before his time.

Carroll’s life began on February 1, 1960. His teenage years were spent in Kainga, on the outskirts of the small Canterbury town of Kaiapoi.

A school friend describes him as a “bit of a loner” with a “phenomenal wit” who never did like to follow the status quo and had a “pretty dim view of authority and protocol”.

Mario Grinwis, 57, went to Kaiapoi High School with Carroll, in the 1970s. Back then his friend was known as Shawn.

“He was so dry and cynical that where the teacher thought he was being respectful and compliant, he was actually in complete disagreement.”

Despite his tough exterior, Grinwis said, Carroll was a loyal friend.

“He was the sort of guy who would do things for you without batting an eyelid.”

Grinwis knew little about Carroll’s home life and they lost touch after high-school. Some years later they rekindled their friendship, online at least, when his old mate launched a search for him on social media a couple of years ago.

In all their chat, Grinwis says his mate never once mentioned being homeless.

“I was quite shocked. I mean, I don’t know if I would have been in a position at all to help, but I would have liked to have known if he needed some assistance.”

The friends lost contact after they left high school in the 1970s.

Carroll left without a qualification in the late 1970s but what he did over the subsequent decades was not something the private man shared – even with his fellow streeties.

Friends say he talked little of the past.

Carroll did not pursue further education for almost 30 years, until he began his tertiary studies at the Waikato Institute of Technology in Hamilton almost 30 years later.

He completed various certificate programmes and eventually graduated with a Bachelor of Media Arts in Journalism and in 2009 was given an award as one of the institute’s top adult students.

After graduation he was meant to start work on a doctoral student’s project, but when the funding fell through Carroll headed for the opportunities he thought Auckland could offer him.

He found the big lights of the city streets – but the opportunities he hoped for weren’t to be found.

Rob, 40, became a good friend of Carroll’s after meeting him in an art class in 2014 or 2015 when both were living on the streets.

He said the reasons why they were homeless were not something they talked about.

“We never really got into that, we never discussed why we were homeless. ‘You’re homeless, I’m homeless, aroha, let’s go for a feed’.”

Rob said Carroll was a great intellect who loved a good debate and would always take a stand for what he believed in.

“Yes he was homeless, but he was an intellect that loves talking to anyone and everyone.

“He would hold the fort, stand up and really tell people what homelessness is about, he’s not afraid.”

It was around 2011 when Carroll became one of the more than 50 human bundles seen huddled against a shop wall, or on a quiet alleyway, within a 3km radius of the Auckland Sky Tower.

His favourite place away from the cold was the Auckland City Library. It was there Carroll could read in peace, use the computers and watch a good movie. Carroll also helped set up a regular free-movie session at the central library for his fellow streeties.

At lunchtime he was often seen at Merge Cafe on K Rd, or at the Urban Vineyard church and at other times could be seen at the Auckland City Mission on Hobson St.Carroll was also a regular at the city council meetings – a quiet, but unfearing voice pushing for change for the growing number of streeties.

Auckland councillor Cathy Casey says his words were always valued. “It’s a huge deal to have street people in front of the council committee. He was a very brave man. He had a lot more to give. “He presented as a grumpy old man. You would walk past him on the street, that’s what you would see.“But he wasn’t [like] that at all.”

She says all it took was getting Carroll to open up with a word of greeting and his eyes would light up and “we’d be off”. “It was really nice to walk into a room and know he was there, he would introduce me to other people.”

Casey says meeting Carroll brought home how homelessness could so easily impact any one of us. “It just takes a tragic life event, that’s Rangi [losing a chance at a job]. “You and me we are only one step removed from homelessness ... that’s what you have to bear in mind every time you see a homeless person.”

“They are just one of us.”

Carroll’s luck began to turn and by mid 2016, with the assistance of social agencies, Lifewise and the Auckland City Mission, he was able to get off the streets.

Getting a shower was no longer a hunting expedition and a hot drink was only a button push away.

Video footage he uploaded to Facebook shows the day he gets his own whare. It’s nothing flash, a single-bedroom place inside the Kiwi on Queen, near the K Rd end of the city.

It has a bed, a table, a washing machine and a shower. It also has space for a TV – one of the first things Carroll was recorded as saying he was going to buy.

“The first priority is I’ve got to get a TV for the weekends. I’m going to bring that back and I’m going to plug that in and get it going,” he is heard telling the person behind the camera.

It was the simple pleasures in life he wanted.

“I’m going to get a jug and make me a hot coffee.

“I’m going to have a long shower, I’m going to turn it on. I’m going to have a very lazy weekend and I’m not going to leave the building.”

Carroll was looking forward to having a home to make his own, a bed to lay in at night and the space to write again.

He became a peer support worker with Lifewise and planned to pay it forward by helping other streeties into a home. Cathy Casey says he was a mentor and role model showing

“I’ve done it, so can you”.

“He got into a home, but his heart was still with the street community.”

“You are only ever five steps away from being homeless and anyone could find themselves in that situation.”

In the night, six months after Carroll was seen first walking through the corridor of his home on Upper Queen St, his hopes and dreams were over.

He was found dead in his bed on April 5, 2017, having died in his sleep some days earlier.

“It was so unfair, he got where he wanted to be in his life, independence, a great outlook ... it’s so sad it was taken away from him by his health,” says Casey.

Friend Jonathan Lyon says Carroll’s death so soon after he finally found a place for himself was one of the saddest things for him.

“In all of that time I had known him, which was over two years, he was on the street, every single day, come rain or shine.

“He finally, finally got into housing and died very soon after.

“The saddest thing was he was so incredibly proud of that place, he wanted to write. It was one of the things he always said he missed, his ability to be in his own space, to have a bed, a table and to be able to write.

“He really felt that 2017 was going to his year.”

Lyon says his friend, who he met while giving a photography course at the Auckland City Mission, would not have wanted homelessness to define him.

He says Carroll would likely have been the first to say he was not without his challenges, he suffered from depression, but “I wouldn’t say it was any further than that”.

“He saw homelessness as an issue, more economic than anything to do with addiction, or any other situation.

“On that basis you are only ever five steps away from being homeless and anyone could find themselves in that situation.”

Lyon says: “I used to try and peel back the layers and try to fully understand the circumstances that led to him being homeless, but he never divulged that.

“Not because he was ashamed, but because it was inconsequential to him, it was a situation he was in, not a part of who he was as an individual.”

Lyon says Carroll “never bemoaned his lot, never played the victim, was always looking to help others in order to help himself, if you will”.

It was Carroll’s steadfast reliability at the many client committee meetings at the Auckland City Mission that meant his absence was quickly noticed when he failed to show one Monday in April.

He was missing.

A call was made to the Kiwi on Queen’s building manager to check and it was then the quiet man who had for five years been a constant presence in the street community was found dead.

Police were the next port of call, and subsequently the coroner’s office, after which Carroll’s body was taken to the local morgue.

A Coronial Services spokeswoman says in the case where a death is sudden, unexplained or suspicious coroners will investigate.

“Sometimes they may make a finding without having to open an inquiry.”

Coroner Sarn Herdson’s later findings showed he could have been there for as long as a week before he was found.

Herdson wrote his official cause of death was internal bleeding brought about by pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas).

Coroner Herdson ruled a formal inquiry was not needed and deemed his death was one “of natural causes”.

But Lyon says there is nothing natural about dying at the relatively young age of 57.

“Truly, for me, it fundamentally points to the long-term impact of rough sleeping and how it eats away at the very essence of an individual.

“The toll it takes for someone sleeping on concrete on cardboard, night after night,” says Lyon.

“I miss him, to this day, I really do miss him.”

Doctor Richard Davies who works at the Calder Centre, where many of the rough sleepers go, says streeties faced a myriad of issues, including many that no longer affected the general population.

He says the constant cold, the lack of sleep, the inherent danger of life on the streets, and the challenges accessing healthcare took a toll on a person’s body and could ultimately lead to premature death, be it from a chest infection, hypothermia, trauma or suicide.

“It’s very difficult to improve health while sleeping rough, it’s not always the highest priority when you are wondering where you are going to be sleeping next.”

At the funeral there were about 30 people who gathered inside the Baptist Tabernacle – the church next to the apartment block where Carroll took his last breath, just days before.

The Auckland City Mission organised the funeral – something it does when family cannot be located or are unable to be involved. Lyon says the only family he knew of was a relative living in the South Island who was unable to make the journey up to Auckland.

“She was a bit shocked [when she heard of his death]. She remembered him as an amazing, kind and loving soul who was misunderstood by his family a little bit. She asked me to put a flower on his coffin for her.”

It joined the cluster of other flowers surrounding Carroll’s casket, which sat centre stage inside the cavernous space of the tabernacle. People walked up one by one, softly laying a kiss on his cheek as he lay unmoving in the open casket.

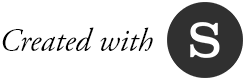

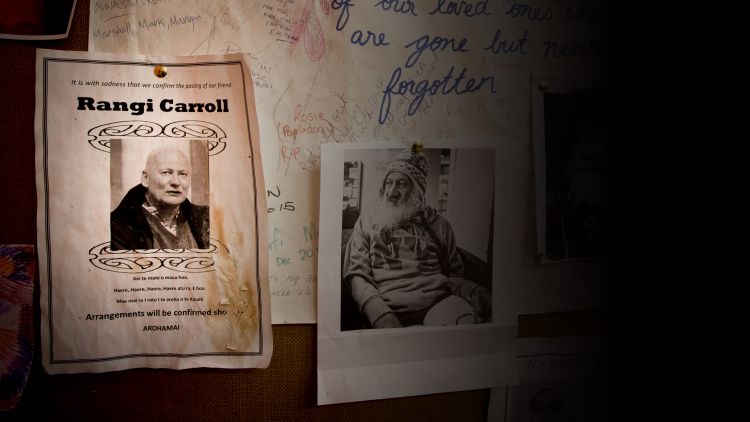

A photo of Carroll, looking out to the camera, was placed near his open coffin. The Auckland Street Choir filled the rafters with song.

During the service people shared their memories of the man with a dry sense of humour, who spoke his mind, was a “bit of a rascal back in the day” and was a good friend many could count on.

As the service drew to a close the lid was put on the open casket, shielding Carroll’s still face from view – the silence was pierced by the sound of a traditional karanga which continued as the coffin was carried outside.

“It was searing, it really kind of punctured your soul ... people were throwing flowers in the back of the hearse, there were lots of tears, it was amazing,” Lyon says.

Just Funerals director Steven Davey took care of the practicalities of Carroll’s funeral; taking his body from the mortuary to the funeral home, doing the embalming and putting him into the coffin, overseeing the service, and eventually the cremation.

He is one of those the Auckland City Mission calls on to organise a funeral – in the event the biological family wants it, or if there is no biological family. Davey estimates he has done eight for the mission in the last two years and says every funeral is an honour.

“We really do think it’s an honour we can do it,” he says. “Basically the mission is a big family, they take care of their own and we take care of the funeral.” It’s not an easy job – nor is it cheap.

According to the Funeral Directors Association of New Zealand the price of a funeral can range from $4000 to $15,000. The maximum grant for someone doing one for a person who has died with no next of kin is $2030.91.

But Davey says even if he got nothing financial in return – it is the right thing to do – a way of giving back to the community. He says every person has a story to tell, which is a privilege he gets to experience each day as an undertaker.

Carroll’s funeral is one that stands out in Davey’s mind.

“A video-clip played at his funeral said, ‘Don’t define me’,” Davey says.

“He said, ‘Don’t define me because of my homelessness’.

“Everybody celebrated what he did and what he stood for, but from my personal view, he was someone that was far too young.”

While the streeties were afforded the privilege of farewelling Carroll, the chance to do so is not something they take for granted. Having a funeral for a loved one and being a part of it is not a given for the street family.

A former homeless woman and elder in the street community, Rose Greaves, gets choked up as she talks about the sense of helplessness they feel when this happens.

“In our minds we are that person’s family, we are the ones that live day-to-day with that person,” she says. “But in general terms we are not and we don’t have any right, really. It means so much [to be included] because we get to say goodbye ... we spend so much time with them and suddenly they are not there anymore.

“So it’s really frustrating not knowing – frustrating and worrying about whether they are sitting on a slab at the morgue. Sometimes there is a lot of anger.”

If the biological family decides to hold a funeral elsewhere, or decides not to include the street family, a memorial is held instead – frequently at St Matthew-in-the-City.

At times the only warning is a mass group text – sent an hour before the service; “Tēnā koutou whānau,” it starts. “Sorry for the late notice”, as was the case when the Herald was invited to attend a service.

It’s quiet as people gather inside to farewell another much-loved member of the street family, a woman in her 50s.

Slipping into the golden pews of the inner-city church they are few, but they sit close to the front, sitting and reading the words on the service sheet. “Sun-rise ... sun-set. The most painful goodbyes are the ones that are never said and never explained.”

In the centre on a table sits a smiling portrait, surrounded by some flowers, the only remnant beyond the memories each person holds close.

The service is simple, led by one of the Auckland City Mission chaplains, a prayer, a few words and at times a warning to those left behind to get medical help if needed and stick to the prescribed advice lest you leave it too late. Those who gather are able to pay tribute – often a brutally honest but nevertheless loving eulogy to who the person was.

In the street community, empty words have no place in a life lived in the open and many in life and death choose frankness over platitudes.

“Tough,

“Horrible,

“Always grumpy,

“Protector of everything,

“Aunty,

“Public nuisance,

“Teacher.”

This ability to speak of the bad, as well as the good, is not a right given to just anyone – but a privilege restricted to the family. If it’s a memorial, the service ends on a quiet note, people filter slowly out and a select few will gather inside the room at the back of the Auckland City Mission dining hall.

The service sheet, and the photo pinned up on the back wall join the faces of roughly 20 others of the street family who remain firmly in their memories even as their bodies go to be cremated, or buried six feet underground.

Photos are equally precious and not kept out in the open for just anyone to view – but out the back of the mission’s main hall, where few people from the general public ever venture.

Inside this room is where the client committee meets each week to discuss matters of the day, events in the community and whatever else is on their mind.

They come in, not always on time. The committee chair, an appointed member of the street community, keeps the meeting on task and matters are swiftly dealt with.

Looking over the business and banter in the centre of the room, from where they have been pinned on the wall, are the faces of those who have gone before.

There’s Littleman Lewis, Whispers, Michael Daley, Papa Jack – people who formed the backbone of their community but whose physical presence has now gone.

Char Paul, 32, says every death from their street whānau is keenly felt.

“In some sense for me, when they have passed away, after being on the street as long as they have, I feel relieved for them because they don’t have to feel the pain and suffering that is out there.”

But she says with each death they are losing a much-loved member of the family.

“We start off with this long chain. If you think about the chain, it’s all interlinked, every time someone passes away that gets shorter and shorter ... but it also grows again as well.”

More on the NZ Herald’s ‘Death on the Street’ series

Homeless in Auckland: A photo essay by Brett Phibbs

Corazon Miller looks at how living on the street is causing people to die young