Crisis for elderly needing care

Radius rest home chain advises families to plan ahead to avoid national shortage of beds.

There is a deep-seated social conundrum poised to affect our elderly: how do we fit hundreds of thousands of people who will need aged residential care into only tens of thousands of beds?

It’s a problem the rest home industry says is already hitting home – and which, if not solved, will sentence increasing numbers of frail, elderly people to a lonely death at home.

The numbers, say Brien Cree, the managing director and founder of Radius (22 aged care facilities around New Zealand), don’t lie. There are about 39,000 beds in the country – beds for frail elderly who need medical treatment and/or nursing help.

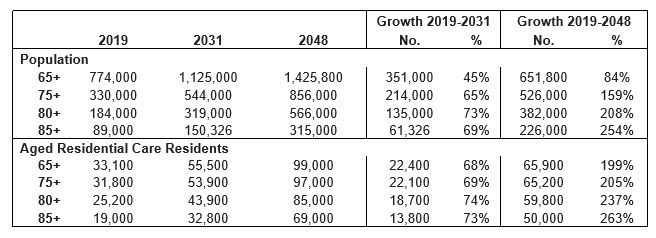

However, our ageing population is set to mushroom spectacularly. Our population as of June 2018 was 4.8m. The latest figures for those aged 65-plus come from 2016: 700,000. Those 85-plus at 2016: 83,000. Fast forward to 2048 and the numbers of 65-plus are forecast to swell to 1.4m, with those 85 and over are predicted to hit up to 315,000, according to research from the New Zealand Aged Care Association (NZACA).

So those 39,000 beds are going to be in demand, particularly, says Cree, if the current shortage of new facilities by the aged care industry continues. The NZACA has forecast there will only be 52,000 beds by 2026.

Reports late last year noted there were 81 retirement villages being built, seeking consent or being planned. That figure of 39,000 beds does not include retirement villages – but they often have more to do with property development and retirement lifestyles than aged care, says Cree.

“Many have some aged care facilities but not very many beds,” he says. “They tend to use care as a marketing tool; an incentive to buy into a retirement village that many people think will be their last move. If their health starts to fail, many will have to shift to a facility like Radius – but the bottom line is that, unless you have additional funds, it is very difficult to move out of a retirement village.”

It’s difficult to plan ahead, he says, as most people want to stay home, but families should try to do so as much as possible for the sake of their elderly relatives, because of the current shortages.

Projected Population and Aged Residential Care Residents*

*Source: Statistics NZ population projections by age, NZACA projections of Aged Residential Care residents based on TAS Quarterly Bed Survey and Aged Care Demand Planner and Statistics NZ population projections

So why is the aged care industry not building more facilities to cater for this wave of elderly? Cree says they simply can’t afford it: “Funding in this sector is so low that existing operators can continue to exist – just – but the margins are low; the returns aren’t sufficient and the funding just doesn’t exist to build care facilities, as opposed to retirement villages.

“We have been lobbying successive governments about this for years but nothing is being done.”

Part of the problem is reports of over 80 retirement villages on the way tend to mask the situation, suggesting the wave of increasing elderly will be comfortably contained on welcoming shores.

“But those retirement villages don’t cater for the vast majority of 65-85 year-olds who have become frail and can’t look after themselves,” says Cree, “or the 85-plus age group who have a higher percentage of people who need care.”

NZACA chief executive Simon Wallace says New Zealand’s property boom has made the cost of land and development difficult for not-for-profit, religious, welfare and charity operators. Retirement villages were able to “cross-subsidise” their smaller care facilities through the cost of the units sold.

Residential aged care facilities do not sell units; most people needing care are on government subsidies – many sell their homes to pay for their care until their assets reach the $230,000 threshold which means the state can pay from that point if they are within income and asset limits.

Cree cites his own mother’s experience – in a wheelchair after a stroke, she was in care for 17 years – as an example of the long-term care many people need: “The reality is that a lot of people need ongoing care. The DHBs do critical care really well – but they are not geared up for long-term care and no one has any more beds. There is a massive shortage.”

“The Northland DHB has 700 people waiting to be assessed for care. They normally have seven needs assessors to do that job. Now they have only two – and they will be stressed out trying to get round 700 people when they can only do about two a day.”

Wallace says the NZACA’s recent report, Caring for our older Kiwis, raised concerns about the ability of many elderly people to access care when they need it. Over half of the country's DHBs are delaying access to rest homes, with potentially serious consequences for their health.

That’s led to what Wallace calls “postcode care” by DHBs, as evidenced in the NZACA report, meaning the ability of elderly to access residential care varies according to where they lived.

It showed that, out of the 21 DHBs, the best admission rate for people in most need of care was only 54.1 per cent (Waitemata DHB), with Bay of Plenty (29.6 per cent) and West Coast (28 per cent) the worst. Only 10 DHBs had an admission rate of better than 40 per cent.

In terms of months taken to get into a residential care bed, it took those people most in need of care an average of 2.1 months (if they lived in the Waitemata DHB area) or 9.7 months if they lived in Hawkes Bay. Only 8 DHBs had waiting times of less than four months.

Cree: “People need to have confidence that we are there and the system is there – only the system isn’t really there and we are facing a future that doesn’t look good.”

For more information visit Radius Care.